The first page in the field of teaching and learning videos in focus

Image by Sönke Hahn based on Sarah Brockmann, released under CC BY 4.0

In the previous parts of this blog series, we provided a basic definition of teaching and learning videos and identified four characteristics: Teaching and learning videos are an audio-visualization that can be accessed independently of time and place, if necessary, and that can be didactically prepared and classified. This was followed by a didactic classification, outlining how and in which scenarios videos can be used. We looked at the multimedia principles that can also be used to optimize learning and teaching via moving images. In the second part, we looked at the 2 + 1 category in the field of educational videos — lectures on video (live, recorded), explanatory videos and demonstration videos. And these categories were placed in relation to the medium of film itself and the techniques used, the forms of production. Now we want to discuss the potential, but also the weaknesses of the use of videos from a communicative-didactic point of view.

Didactic-communicative potential of educational videos

For the sake of clarity, we differentiate between three potentials: basic potentials, potentials in the overall didactic mix and potentials from a production perspective. Basic potentials result from the nature of the medium, potentials in the overall mix relate the moving image to other teaching and learning measures; “production perspective” refers to practical potentials in the realization of teaching and learning videos.

Basic potentials

- “Working memory-compliant” communication: Addressing the audience in a multimedia way, i.e. using visual and acoustic channels, can increase the chance of communicating the intended content — without overloading or overloading the working memory. See multimedia principles and their background in the first article. The person producing the content must weigh up the options and find a good balance with regard to measures that promote learning: Teaching and learning videos are conducive to learning if spoken statements or explanations are presented as synchronously as possible with the visualizations (≈ temporal continuity principle). On the one hand, sound and image should not be too far apart (≈ principle of coherence). Otherwise, learners may lose their orientation. On the other hand, for example, it should not be read out loud, i.e. a 1:1 pronunciation of readable, i.e. shown texts (≈ redundancy principle). Such a procedure can lead to a load that is difficult to synchronize with regard to visual and acoustic resources or our working memory.

- Promoting individual learning, independent of time and place: Today’s videos, which are mostly digital and placed on the Internet, intranet, etc., can be accessed by learners at any time or place — just like other digitally provided materials/media. This means that a video, the content documented there, can be viewed several times etc. The situation is different for live broadcasts, which do not provide for recording. In the case of live broadcasts, however, the non-repeatable event character could be emphasized in order to motivate viewers to tune in.

- Vivid communication of contexts, even spaces: Educational and explanatory videos have the potential to make facts clear and to demonstrate contexts. Although this potential is primarily attributed to 3D animations and/or naturalistic design approaches (Zander et. al. 2018: 10), we want to generalize: Analogous to the sequential nature of the medium of film, sequences or processes are particularly suitable as content for videos or can be depicted in short videos (Harder n. d. 102) — as a fusion of content and form. The moving image also holds potential due to our familiarity with it, insofar as we can create spaces from individual images and shots in our mind’s eye. From an early age, we have learned to unconsciously translate the information presented by pans and cuts into a spatial concept. Even without stereoscopic 3D and without 360° films, we virtually immerse ourselves in the resulting space (Hahn 2018) and thus in any intended teaching content. Specifically, we can list some means that could be used in the design of teaching and learning videos. Linguistic or visual highlights can be used to utilize the space in the screen. Orientation is provided by so-called deictic cues, which use the spoken text to create a concrete reference to the images — similar to the lecture hall, when reference is made to the content of a slide: “Here below you see now”, “right next to it” or “this symbol shows”. Alternatively, visual highlights such as color or typography, arrows, circles or animation effects can also be used to draw attention to the content(signaling principle).

- Manipulate time and make it visible: In addition, content that captures a temporal dimension can also be depicted. Let’s think of chemical reactions that take a long time or occur quickly to the naked eye. Here, too, it is possible to depict processes or states by means of slow or fast motion — slow motion and fast motion.

- Virtual substitution of the human medium? We have already seen in the first part that a human or human-like presence can be helpful: For bonding teachers and learners with each other and with the content. Can do no more, no less — especially with regard to constructivist perspectives. In addition, beyond the direct promotion of learning, an indirectly learning-promoting strengthening of a relationship of trust between teachers and learners can certainly be promoted by a balanced (visual) appearance of the lecturer. Imagine this: Sitting in the lecture hall without seeing the person giving the lecture is likely to seem very alienating (and could even pass as a crisis experiment). In practice, a live transmission from one seminar room to a second is a possible solution if space is limited, although this cannot completely do without the protagonist either. However, the situation is different in explanatory or demonstration videos; here, the visual presence of a presenter is not necessarily required. This aspect should also be examined from a communicative-didactic design perspective. The central question here is: “Does the visual presence of the person speaking have a beneficial effect on the learning process?” To date, there are no clear empirical findings on the extent to which the presence of the speaker in teaching and learning videos has an impact on learning. Schmidt-Borcherding and Drendel (2021) ask about the significance of this presence and address the competition between the elements used and speaker images for the attention of learners. The person speaking receives 30% of the visual attention. Their effect in the image must be assessed as ambivalent: “On the one hand, the speaker’s presence attracts attention and can thus distract from the learning object. On the other hand, a visible speaker can draw attention back to specific aspects of the subject matter.” (Schmidt-Borcherding/Drendel 2021: 71). The mere visualization of a speaking person is therefore less decisive than the question of how and when they actually appear in the video. The overall coherence of the multimodal elements used (image, sound, image of the speaker) is therefore important (Schmidt-Borcherding/Drendel 2021: 71), which touches on a communicative-didactic problem: The decision as to whether and how a visualization of the speaker is realized cannot therefore be answered in a general way here. At this point, the use of a storyboard for planning a teaching and learning video is recommended in any case in order to weigh up and record such decisions. Here is an invitation to browse through the collection of teaching and learning videos. Speaking of substitution: At this point, we should not fall for the misconception that a virtual get-together is on a par with face-to-face contact. Certainly, in the wake of the pandemic, it can be seen as a substitute to compensate for not being able to meet in person. Nevertheless, the excerpt-like character of a video leads to a different, less comprehensive communication (body language etc.) in relation to a face-to-face meeting.

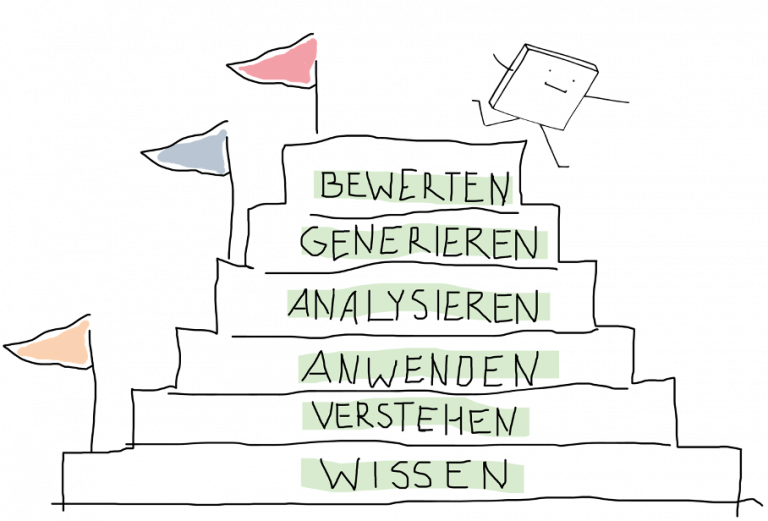

Linking learning objective taxonomy and teaching and learning videos

Image by Franziska Bock based on Sarah Brockmann, released under CC BY 4.0

Excursus — teaching and learning video + learning objective taxonomy

When we talk about didactic potential, the taxonomy level model comes in handy at this point. The taxonomy of learning objectives has already been touched on in the first part of this blog post. The aim here is to relate the six classes of cognitive learning objectives to the medium of teaching and learning videos. The use of teaching and learning videos can also be very diverse from a didactic point of view. However, diversity should not necessarily be taken to mean arbitrariness. The use of teaching and learning videos should never be an end in itself. Rather, they should be used as a means and selected for good reason as part of the conceptual curriculum planning. At best, teaching and learning objectives are the starting point. Based on the specific learning objective linked to the question of what students should actually do (methodologically), the teaching and learning video can be linked to the different learning objective levels. Of course, this can only be done here in a very general and exemplary way.

- Remember knowledge / retrieve knowledge — Regardless of whether the video material is self-produced or produced by a third party, a task is implied in both cases; the teaching and learning video has the character of an invitation to receive what is presented. At the first stage, an educational video can be linked to the intention of initially receiving content in order to acquire the information it contains as knowledge. This often involves knowledge of individual facts, sequences or terminology in the mode of explanation. These aims are constitutive for explanatory videos, but also for instructional recordings. “The underlying didactic approach is based on the provision and distribution of information.” (Seidel 2018: 48) However, pure reception does not always lead to success. Occasionally, a didactic or methodological framework is required that goes beyond mere reception. For example, additional elements such as knowledge queries or control tasks can be included. Whether in advance, during the course of the video or afterwards, questions or tasks can strengthen the focus. With the help of some applications, depending on the platform for publishing a video, an explanatory video can be divided into meaningful sections. For example, a task could be added at the end of a video in addition to the finished file — H5P. The boundary between the first and second stage is fluid.

- Understanding: For the cognitive learning level of understanding, it is advisable to allow the information presented in the teaching or learning video to be reproduced beyond viewing. Students should recapitulate the central statements in their own words or write a summary. As a possible scenario, a video can also act as a silent stimulus for introducing a topic in order to activate any prior knowledge. It can already be seen here that the learning requirements required here refer to the first level (remembering/knowledge) and take the considerations there with them — as already mentioned, the levels are not free of overlaps.

- Apply: The Apply learning objective level can also be designed differently in conjunction with teaching and learning videos. For example, a case can be used as demonstration material and function as a concrete self-learning activity. It is also possible for the Apply phase to be preceded by a video, which would, however, be described as an instruction: video instructions, also referred to here as tutorials, provide instructions on how actions and processes are to be carried out (Seidel 2018: 47).

- Analyze: However, teaching and learning videos can also be used as an object of analysis and, in the form of a demonstration video for example, reproduce “natural” situations or action situations that students can approach with their analysis categories: Perhaps a conflict is shown, on the basis of which escalation stages are to be clarified or possibilities for intervention can be considered. On the other hand, videotaped actions can serve as interpretation material to promote a corresponding ability. This can or should always be done with media literacy in mind: Like all media, film can only ever depict an excerpt.

- Generate: We have already addressed the learning objective of generating several times with examples of filming or producing your own videos and with the “learning through teaching” approach. Students are given the task of preparing a learning object in the format of a video and making it available as information material for the learning group: Video glossary, explanatory video, on a term, presentation of a concept or model or of theorists, etc. This approach allows students to take a look at the media characteristics of the moving image and strengthens their skills in communicating facts to others. In this regard, however, teachers must provide support measures for video production and take into account the resources available to students.

- Assess: Video resources can also be used as an object of reflection. First of all, the self-produced video could be reflected upon — see above. Overall, contributions from various areas can be used to analyze, reflect on and evaluate the recorded cultural forms of expression: What does a history film say about the worldview during the production of the film and the anticipated worldview of the target audience? What did people know about the history covered? Videos are — similar to analyzing — demonstration material. (As I said, there is never any overlap between teaching and educational video types.) Demonstration videos can provide key impulses for the learning process — for discussions and in-depth debates; not least, they promote multiple perspectives and, depending on the focus, critical thinking.

These are just a few examples to show that specific learning levels can be anticipated with and in the design of teaching and learning videos, depending on the didactic function and intention. However, a rigid transfer is not advisable. Rather, the aim here is to provide a rough orientation for their use.

Potential in the overall didactic mix

- Supplement and deepen: Due to time constraints during the contact phases, for example, topics that have only been touched on can be made available to learners in an individually accessible video, for example as part of a learning platform, to supplement and deepen any content. (Sailer/Figas 2015: 78; Aldrian 2019: 4 f.)

- Preparatory and follow-up sources, summarizing function: Especially in the context of flipped or inverted classroom, but also online courses, videos can be one or the basis to prepare for the later contact time, the exchange about the source material (Aldrian 2019: 5). Videos can also be of a summarizing nature, for example at the end of a course (Aldrian 2019: 5). In their summarizing function, they can also rhythmically structure individual sections of an event in advance: See below and furthermore multimedia principles.

- Be the ‘driving force’ — create an incentive, offer an introduction. Videos are suitable for introducing learners to a subject. This is because they correspond to the “media usage habits of learners” (Harder n.d.: 102). Especially at the beginning of a series of events, elaborate and captivating videos are likely to be advantageous, as they can have a pioneering character, as a first impression to encourage the learner to stick with the course.

- Variety, rhythm — diversity as an element of “good” teaching: Certainly not exclusive to the moving image, a “different” medium or video can offer variety, for example by introducing it into the theoretical phase of a course, according to Aldrian (2019: 5). The use of instructional and explanatory videos can also be understood in terms of the definition of good teaching (Meyer 2020): a video as a “mesodidactic” (Meyer 2020, 74 ff.) methodology. Methodological and media diversity can contribute to maintaining or regaining the attention of learners on the part of teachers.

- Learning through teaching (Ebener/Schön 2017: 4): Videos realized by students can be used to teach other students. This approach gives students an insight into the media characteristics of the moving image (≈ media literacy) and strengthens their ability to communicate facts to others. In this regard, however, teachers must provide support measures for video production and take into account the resources available to students.

Potential from a production perspective

- Picking up on the familiar (≈ medium of film) on the part of learners: Educational and explanatory videos offer potential due to their conventionality — we grow up with moving images from an early age and the proportion of videos on the Internet has been growing for years. In this respect, it is not necessarily necessary to learn to understand films; basic skills are already available. Despite the improbability of communication, which also applies to teaching and learning, at least a first hurdle in the sense of opening doors can be overcome in this way.

- Adaptation to specifics/target group through own production: Instructional and explanatory videos produced by yourself can offer the potential that you as the producer can specifically address specific facts and topics as well as the respective target group and their situation; you do not necessarily have to fall back on ready-made materials. Once a project file has been created, it can be changed/adapted if necessary — albeit not without effort.

- (Efficiency on the part of producers — through retrievable data sets, versionable project files): Recordings of teaching events allow for efficient teaching insofar as the material can be used multiple times — initially on the part of learners: videos can be viewed, stopped and rewound multiple times (Rosenbaum 2018; Aldrian 2019: 6). Recordings of lectures can facilitate preparatory and follow-up work — inverted classroom (Aldrian 2019: 6). In general, and not only in the context of the pandemic, educational videos offer the opportunity for individual teaching and learning that is independent of time and place ≈ asynchronous teaching. Teachers can use materials multiple times — in the next semester, for example. Materials can be adapted — with more or less effort. OER materials can develop potential in terms of efficiency and, if necessary, the targeted adaptation of a video: If they are open file formats, i.e. in the case of video primarily project files, including integrated or linked, freely licensed files. The brackets around the term efficiency result from the fact that film production can be described as complex and/or resource-intensive.

Excursus (OER) openness and the moving image

OER, or Open Educational Resources, are regularly associated with the term openness. This is because, in the spirit of OER, materials can be reused and even edited by others through openness, depending on the license. Ideally, open file formats should be used for storage so that reusers can easily adapt or even expand the material to suit their needs. But what does open mean specifically for the field of video? Not exclusively for video, but mainly due to its multimedia nature(at least sound and image etc.), films could currently (state of the art) always be understood as closed: The individual elements from which the video is created cannot be extracted from the final file and edited separately without effort, or sometimes not at all. “Non-exclusive” has anticipated this: Basically, this also applies to image files — such as a JPEG or a PNG. In the context of videos, open can therefore primarily mean that the video file is saved in a format that can be opened by as many subsequent users as possible — in the sense of playability. If the video is to be provided with interactivity via an H5P plugin, the video should be available in MP4 or Webm format, for example. And: It is meant that the video file can be opened and cut etc. by common video editing programs. Ideally, in the context of videos and OER, open means that the project files of a video / the editing software, including the elements linked in this project file, can also be uploaded to an OER platform. This would allow users to access individual elements such as music, sound effects, embedded graphics and the video material itself. Restriction / for the sake of transparency: However, this process is associated with considerable effort for the uploading person / author.

The challenges in the field of teaching and learning videos

Image by Sönke Hahn based on Sarah Brockmann, released under CC BY 4.0

Critical comment on the use of instructional videos

Not only in this, but also in the previous parts of this blog series, it has been repeatedly mentioned that the use of teaching and learning videos, despite their great potential, sometimes poses challenges for both learners and teachers. Or that educational videos do not always promote learning — we would like to share three critical comments with you:

- Sequentiality of the medium: It is both an advantage and a disadvantage — the nature of the medium itself. Film is a sequential medium: individual images follow one another. This means that a movie can never be viewed ad hoc. It is necessary to scroll through the file, as far as possible, in order to be able to grasp all facets and then only in an overview. Printed material, on the other hand, can be viewed without any major technical equipment or infrastructure. On the other hand, a sheet as such can be captured quickly. However, the page can at best depict processes in a catchy or definitive way in the sense of a flip book — as pages of a book. (Of course, it can be argued that a page, like a single image, is often enough ‘only’ part of a sequence. In addition, the higher resolutions of the moving image should make it possible to depict similarly comprehensive information in the video in the long term).

- skills (and budget on the part of the people producing the videos): The production of even short videos is usually time-consuming and requires basic knowledge of design and narration. These skills regularly go beyond those of mere consumption. It is no coincidence that there are corresponding degree courses in moving image and/or audiovisual design. On the other hand, knowledge of both the software in question and the technology required must be taken into account. The same applies to the budget and the time required to produce an educational or explanatory video. Explaining something ad hoc is generally out of the question, despite powerful smartphones. An awareness of the connection between form/how and content/what is necessary: Not only should a video be designed, realized and used with an overarching teaching concept in mind, the video itself should also correspond to didactic and/or communicative considerations and levels of knowledge. Every medium, including film, is based on an inseparable relationship between form and content. In other words, successful content can suffer from an ill-considered form — because it may then not be able to win over learners or pick them up in their world in a vivid and target group-specific way. Then: Although a human need for aesthetics (Maslow — more on this in a moment) can be assumed, an excess of purely decorative elements can be distracting (Mayer 2021: 143). In concrete terms, as seen in the first part of this blog post, it is advisable to take a look at the so-called multimedia principles in order to weigh up or even reduce sound-image clashes and minimize the overloading of the same information on different channels (≈ 1:1 pre-reading).

- Growing expectations on the part of the audience/learners: Experience has shown that the spread of moving images increases the expectations of the audience, i.e. learners. Pixelated or acoustically unsophisticated content is therefore more likely to be demotivating than fully appreciated. A higher technical quality should also contribute to the understanding of the intended content, as the sound and image can be better grasped and are not in danger of being lost in a mishmash of pixels (Aldrian 2019: 6). Low-quality materials are also likely to be of limited long-term use — for teachers and learners. Certainly not every video needs to be realized in 4k or 8k resolution. If possible, FullHD (1080p) should be achieved now (2022). In addition to a certain technical and technical value, aesthetics must also be understood as an added value in the context of teaching and learning: The need categories of the US-American psychologist, Abraham Maslow (1970: 51) suggest that aesthetics is a human need. Aesthetically successful works are held in higher esteem (Yablonski 2020: 59 ff.).

- Reduction trap — too simple: In order to comply with any (albeit questionable) rules of thumb regarding the ideal length of a video, to counteract the media noise of our time, to produce crisp teaching units in video form, there is a risk of conceived content being shortened excessively. There is a risk that the intended content and its complexity will not be adequately grasped by learners (Ebner/Schön 2017: 7) because it does not prove to be a challenge. This field may also include the fact that reduction, understood as simplification, can cause learners to overestimate things: “Everything seems so simple.” The concept of flow from the 1970s in the sense of the Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Robert Csikszentmihalyi (1990) suggests that a kind of balance between requirements and abilities should be kept in mind in our case of learners — in order to promote said flow. In a moderate version, this can be understood as a comprehensive experience of concentration. In this respect, progression in this direction should be achieved either in the course of a series of teaching units and instructional videos or within a video with increasing content and/or audiovisual challenges: This is because anything too simple can demotivate rather than encourage people to stick with it — analogous to those challenges that, because they are not appropriate for the target group, cannot be mastered at all. A gradual increase can be achieved between the two extremes in order to promote the aforementioned flow.

Conclusion

Instructional and explanatory videos offer a wide range of potential in teaching and for learning — they are universally familiar by convention; didactically, their multimedia and sequential nature offers opportunities to teach in a more catchy (process-like) way, to make time visible; as retrievable files, they can promote asynchronous, generally individual teaching and can be used on several occasions in the long term. However, the use of educational and explanatory videos also presents teachers with challenges — in terms of narrative and design skills, budget, time and technology. At the same time, it is worth getting started in this field because, as with many skills, it is possible to build on an initial basis in further projects and skills grow from project to project. This collection of templates and handouts for video production on twillo.de offers concrete help with production, from conception to realization. This was created in line with the didactic orientation of the OER platform twillo to support teaching. In addition to the types, the collection explains the workflow and supports the creation of a tension sheet, the writing of a script and/or the creation of a storyboard — using templates and handouts. In case you missed the first two parts:

- Part I: Characteristics and didactics of instructional videos

- Part II: Formats and fields of educational videos

About the authors

Franziska Bock, M. A. and Dr. Sönke Hahn are research associates of the project “OER-Portal Niedersachsen”: twillo — Lehre teilen. Bock is active in the field of university didactics and deals with questions of writing didactics and the conception of reusable teaching and learning materials. Hahn is an interdisciplinary scientist, filmmaker with international performances and multiple award-winning designer. As part of the Emden/Leer University of Applied Sciences, Bock and Hahn see it as their mission to go beyond good content to advance teaching as such.

References

Aldrian, S. (2019): Teaching video. Center for University Didactics. University of Applied Sciences of Business, Graz. URL: https://www.campus02.at/hochschuldidaktik/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2019/09/Lehrvideo.pdf (retrieved on 15.03.2022).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990): Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Ebner, M. / Schön, (2017): Learning and teaching videos: Design, production, use. E‑learning handbook. 71st supplement (October 2017). 4.61. S. 1–14.

Hahn, S. (2018): The sixfold nature of immersion: an attempt to (discursively) define a multi-layered concept URL: https://www.academia.edu/35937976/Die_Sechsfalt_der_Immersion_Versuch_der_diskursiven_Definition_eines_vielschichtigen_Konzepts (15.03.2022).

Harder, S. (n.d.): Teaching videos. Possible uses in part-time studies. URL: https://www.uni-rostock.de/storages/uni-rostock/UniHome/Weiterbildung/KOSMOS/Lehrvideos.pdf (retrieved on 15.03.2022).

Maslow, A. (1970): Motivation and Personality. Harper & Row.

Mayer, R. E. (2021): Multimedia Learning. Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, H. (2020): What is good teaching? Cornelsen: Berlin

Rosenbaum, L. (2018): “Youtube — Developing educational videos into an interactive learning experience” In: Blog E‑Learning Zentrum Hochschule für Wissenschaft und Recht Berlin. URL: https://blog.hwr-berlin.de/elerner/youtube-lernvideos-zu-einem-interaktiven-lernerlebnis-weiterentwickeln/ (accessed on 15.03.2022).

Sailer, M. / Figas, P. (2015): “Audiovisual educational media in university teaching. An experimental study on two learning video types in statistics teaching” In: Educational Research 12 (2015) 1, pp. 77–99.

Schmidt-Borcherding, F. / Drendel, L. (2021): “Explanatory videos in digital university teaching: What role do speaker presence and coherence play for learner learning and learning success?” In: die hochschullehre, 8, pp. 69–76.

Seidel, N. (2018): “Task types for the interaction of e‑assessment and learning videos” In: Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg (ed.): Videocampus Sachsen — Feasibility study, pp. 45–60.

Yablonski, J. (2020): Law of UX. 10 practical principles for intuitive, human-centered UX design. O’Reilly/dpunkt: Heidelberg.

Zander, S. / Behrens, A. / Mehlhorn, S. (2018): “Explanatory videos as a format for e‑learning” In: Niegemann H., Weinberger A. (eds.): Learning with educational technologies. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg.

This article by Franziska Bock and Sönke Hahn is licensed under CC BY 4.0 unless otherwise stated in individual content.