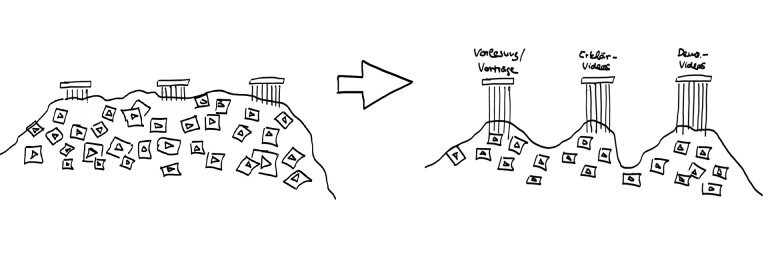

Last time, we provided a basic definition of teaching and learning videos and identified four characteristics: Teaching and learning videos are an audio-visualization that can be accessed independently of time and place, if necessary, and are didactically prepared and classified. We have classified them didactically and outlined how and in which scenarios videos can be used. With the so-called multimedia principles, we have become familiar with a catalog that provides orientation in order to optimize the design of videos with a view to learning. Now we want to look specifically at the 2 + 1 categories in the field of teaching and learning videos that have already been outlined — lectures and (specialist) presentations on video (live, as recordings), explanatory videos and demonstration videos — and relate these to production forms.

One side of the coin: the three format categories — now it’s all about the formats within these categories

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC 0 (1.0)

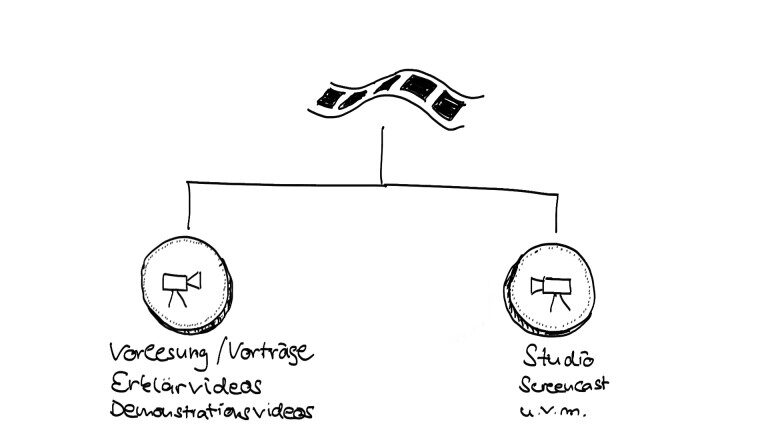

First, we want to locate the three pillars within the medium of film. We will then describe specific formats within these three pillars. And then contrast these with the techniques and processes used. These methods and techniques mark the second side of the coin in the field of teaching and learning video — we have already touched on them with concepts such as animations or screencasts.

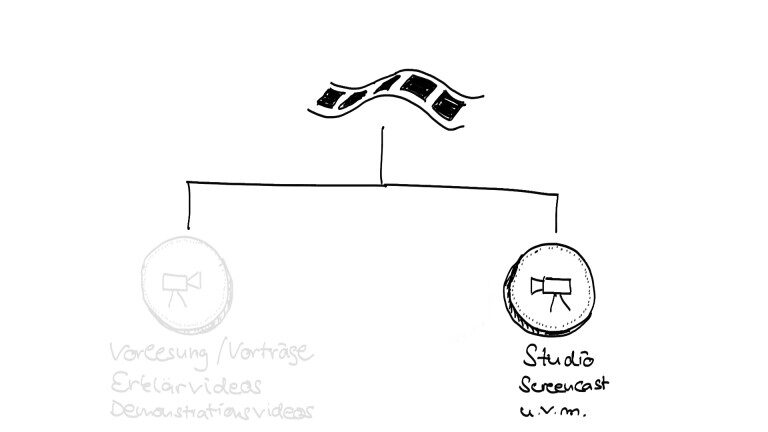

Familiar to us from the first part of this blog series: the field of teaching and learning videos as a whole — both sides are defined in more detail below.

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC BY 4.0

The explanations are preceded by a usage note: It is certainly advisable to start with the overview of formats and procedures as a whole in order to gain background knowledge. Nevertheless, and this is why the table of contents now follows, it would also be possible to search for specific formats or to select the relevant knowledge directly.

Classification of the formats of teaching and learning videos in the field of moving images

In order to refine the basic definition given in the first part of this blog post and the type categories outlined there in the field of teaching and learning videos — lecture, explanatory videos, demonstration videos — and to name formats, it is worth taking a brief look at the moving image as a whole. In this way, teaching and learning videos can be placed in a larger context, the medium of film.

One of the “most important distinguishing criteria” (Kamp 2017: 142) in the classification of the moving image is the differentiation between “fictional” and “non-fictional”. “Fictional” refers to scenic productions, while “non-fictional” refers to the documentary examination of what is colloquially referred to as reality (Kamp 2017: 142 f.). The aim of non-fictional formats is to show facts and their facets in a factual, clear and concise manner or to make them accessible to the audience (Kamp 2017: 145). Educational videos are therefore likely to formally belong to the non-fictional complex.

In practice, it is almost impossible to make this distinction without overlaps — even when it comes to educational videos. That is why we have spoken of “formal”. Because fiction naturally deals with reality, albeit on a different, content-related level, just like non-fiction: even a science fiction film can (and must) deal with topics from our everyday lives (in order to find an audience), deal with social problems of the present — despite (or precisely because of) the detour via an imagined future. Abstraction can therefore certainly offer the potential to approach a topic from a distance — in teaching, in audiovisual formats.

In this respect, but also beyond this, the following formats should not be understood as irrevocable with regard to the conception and production of educational and explanatory videos and used accordingly. After all, a look “outside the box” can provide inspiration — in line with the multimedia principles outlined in the first part of this blog post : feature film sequences can enrich historical documentation (≈ reenactment — Kamp 2017: 149), so that “only” verbal information can actually be illustrated (Kamp 2017: 145). An illustrative story, avatars and the appearance of the person giving the presentation can also support the neutral communication of a subject matter and foster loyalty to the subject matter on the part of the audience, in our case learners (≈ personalization principle).

We have already touched on the formal aspects of the story and the speakers appearing, over and above the content potential of the moving image. With regard to form and content, it must also be noted (with a view to the first post in this blog series: again) that they are practically inseparable. One potential of film, understood as so-called live action footage or real footage, is that it can depict topics “as they are” at first glance. (For the sake of completeness, however, it is important not to fall prey to the common misconception that photorealistic images are the same as truth or reality. Every medium has its own characteristics and so a film shot is always only a section that is more or less consciously chosen and therefore always omits or has to omit one piece of information in favor of another).

On the other hand, animations (apart from photorealistic, nowadays often computer-generated forms) would be more suitable for depicting complex issues: “In this context, it has been shown that a schematic simplification of visual learning content is conducive to the conceptual acquisition of knowledge compared to realistic representations” (Merkt/Schwan 2018: 2). However, if the content depicted is to be recognized in the real world (medical tools, etc.), realistic images should be considered (Merkt/Schwan 2018: 2). The degree of abstraction or realism of a teaching and learning video must therefore be weighed up on a case-by-case basis.

However, the aforementioned theoretical distinction between fiction and non-fiction is softened simply by the fact that documentary as a specific form belongs to the documentary or non-fictional formats (e.g. Kamp 2017: 148 f.). Documentation is therefore a sub-form of documentary. Or, more specifically and as an anticipation, a screencast can be both documentary in nature and promotional beyond instruction ≈ an insight into software before it is purchased. Applied to education, a subject matter, a method, etc. can be made “palatable” in this way, even if it is certainly not necessarily of a potentially lurid nature. Without losing sight of the noble goals of teaching, it is advisable to be aware of the fundamentally similar communication mechanisms in the fields of education and “commerce” and, if necessary, to take them into account.

Industrial films and image films are also likely to be complex in terms of fiction and non-fiction: On the one hand, technical aspects or functions should be explained soberly, while on the other hand, these formats are often intended to promote a product (Kamp 2017: 150). An image film as a whole, and not just part of its structure, can be understood as a teaser that is intended to whet the appetite for more (Kamp 2017: 150). This touches on an old method of building up films and stories beyond the moving image, which is also used in educational videos and corresponds to the zeitgeist: this refers to the teaser or cold open, something called a hook, which is intended to provide an introduction in medias res. The immediate access designed by the producer is intended to arouse interest and/or explain what is to come and its added value, so that in the face of media noise or oversupply, an audience is more likely to “stay tuned” — also with regard to educational videos.

The two sides of the coin in the field of teaching and learning videos

Despite the foreseeable vagueness in the definition of the formats of educational videos (in the first part of this blog post and in the distinction between fiction and non-fiction), it makes sense to divide them into different formats. This provides an overview. These formats are the first side of the coin.

However, in order to give expression to the obvious complexity of the complex of educational and explanatory videos, we will contrast the educational and learning video formats with a second pole — as the second side of the coin. As already mentioned, we also encountered this second field in the first part of the blog series with reference to the means used in video production (animation, screencast, etc.).

In the following, we will therefore start from the different formats and often associated roles of the authors — on the one hand, you as the producer and your intentions during the preparation of a subject matter in video form. On the other hand, production methods and the technology used in the realization of a film or the different elaborate processes will be taken into account.

Overall, the aim is to raise awareness of an important area of tension in the planning and production of teaching and learning videos — an area between economy, intention, skills and resources.

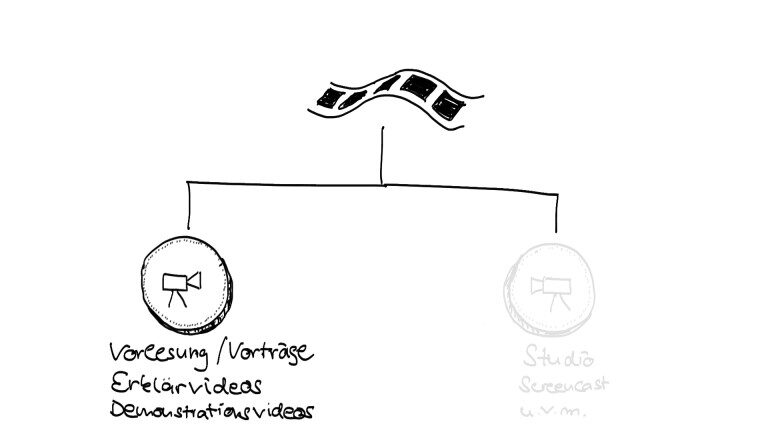

The first page in the field of teaching and learning videos in focus

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC BY 4.0

Page 1: Formats and intentions

At this point, we encounter the three format categories already mentioned several times — lecture/lecture, explanatory video, demonstration video. We already introduced them in the first part of this blog post. In the following, we will specify these three pillars as far as possible and appropriate. The terms instructional and educational video continue to serve as a generic term.

Recording of lectures and presentations

As announced, the poles in the field of tension between teaching and learning videos cannot be strictly separated. It therefore makes sense to explain this first format category in the field of educational videos by looking at the production perspective. Three forms can be distinguished:

- Recording of a lecture or presentation held in front of a live audience — as a file or streamed live. This is also referred to as a “live digitized lecture” (Persike 2019: 4).

- Broadcast of a lecture from a studio, which in turn is streamed live and/or recorded for later retrieval (two to three flies …).

- a pre-produced unit, without live streaming. This process is also referred to as an “e‑lecture” (Persike 2019: 5, Harder n.d.: 103): They can or should be of a high-quality nature. In addition, they are considered shorter and more focused compared to the recording of a course (Persike 2019: 5, Harder n.d.: 103).

The recordings of entire lectures offer the potential to attend a course independently of time and place. There is also the didactic advantage that the material can be stopped or viewed again and again (Rosenbaum 2018: n.p.). The recording offers follow-up potential (Aldrian 2019: 5) if the content of the live lecture or classroom lecture needs to be deepened or repeated. The situation is different for live lectures that are streamed. However, if no later publication or recording is planned, these can still be viewed regardless of location, so that it is not necessary to come together in person, on site, in presence.

The recording of a face-to-face event tends to allow long-term use of the same event ≈ efficiency — from the point of view of the teacher. However, depending on the resources available, a filmed event can appear unpolished in terms of image and sound and not always be ideally comprehensible: “incidentally” filmed slides brought in by projector on site can become illegible in the video file — especially if the event is captured from a distance without a second, close-up camera shot, without zoom, etc. For further use, it may therefore be appropriate to edit the video to compensate for lengths or ambiguities. However, this should not result in a patchwork quilt — a subsequent one-off insertion of a slide, otherwise “only” one view of the room, slides and person giving the lecture, is likely to cause more irritation than sense.

Overall — despite all the economic potential according to the motto “two birds with one stone” — it should be pointed out that an e‑lecture and a face-to-face lecture are quasi different media, they are two media forms in the field of lectures etc.: The dynamic in presence, the physical effect of the person giving the lecture on an audience on site tends to be lost in the recording, based on the cropped framing — similar to how the legibility of the slides is risked in the context of a video filmed from a distance, from behind the room. Modern webcams with autotracking, panning and zooming functions can compensate for these differences to some extent, as the camera automatically follows you as the person giving the lecture and can be controlled by gesture, i.e. without additional helpers, such as zooming. Nevertheless, it remains the case that the slides presented via projector can only be read to a limited extent: A live broadcast of a face-to-face event therefore requires a slide design with large font and little text. It may also be necessary to release the materials in parallel, e.g. using the screen sharing function of conference software, or to integrate the slides in post-production at a later stage. In this sense, neither of the two media can be completely satisfied. In this respect, live presentations on site differ from those via stream in terms of planning, implementation and reception. And both fields must be distinguished from pre-produced content:

A pre-produced teaching unit deviates from the concept of “several flies”. Initially, a lecture is usually given without an audience. This offers the opportunity to create a high-quality audiovisual experience: Instead of being filmed from a distance and possibly captured with a microphone permanently installed in the camera, it is possible to interact acoustically clearly with the imagined audience on the other side of the lens (for appearance’s sake) during the filming by using a clip-on microphone and/or boom pole. This allows the speaker to be brought more into focus. In this way, a closer relationship can be achieved with the (later) audience. This can also foster a bond with the subject matter being conveyed (≈ personalization principle). In any case, passages can be repeated and re-recorded if they are disliked. Caution: An overly trained, stilted style of speech has an artificial effect and can disrupt the bond in terms of the personalization principle. The slides can be combined with the speaker’s material in high resolution via editing or image splitting (picture in picture, split screen, etc.). And even if only one camera is available, it is still possible to change settings for variety and didactic purposes: The recording allows interruptions for rebuilding, so that important information can be added from close up and made more comprehensible for teachers.

Recorded live streaming in a studio environment turns out to be a hybrid. Initially, this method without an audience benefits from better lighting and more eye contact with the virtual audience. If different shot sizes were to be used during live broadcasts, automated, gesture-controlled cameras, multiple cameras or assistants would be required. However, even if bloopers and possible lengths “happened” during the live streaming, the excellent material can be used to tighten up or even — thanks to the consistent studio situation — partially re-record any passages without the audience watching the video file noticing.

For the sake of completeness, please refer to the video podcast. It is considered a sub-form of the e‑lecture (Persike 2019: 5). A video podcast is initially a lecture produced with little effort that captures a person or an exchange between several people on a specific topic (similar to an interview) without a lot of image changes. A flipchart or whiteboard can be used for this. This can be used to develop topics in a (simulated) dialog with the virtual audience. The “usual” classroom or office can serve as the setting for the “filming”. However, the transitions to more elaborate design approaches (studio) and other formats are fluid. Similar to purely acoustic podcasts and their transitions to radio plays, musical, pre-produced or even staged content can be added (planned) afterwards, for example.

Explanatory videos

As the first part of this blog post should have made clear, there is no single definition of explanatory videos. There is no doubt that explanatory videos are shorter than a recording of a lecture; compared to a recorded face-to-face event, they are likely to be more elaborate in terms of animations, music and transitions. Ultimately, a length of between 1–20 minutes can be assumed (Harder n.d.: 103. and Ebner/Schön 2017: 3). The “nugget” mentioned in the introduction to this second part of the blog post can be understood as a very short (not only) videographic teaching unit. It can therefore be assigned to this format category. Overall, classic formats that fall into the explanatory video category — reportage, report, etc. — are likely to be longer in analogy to cinema and television, or such a length may be familiar to learners from habit (again cinema, television). In anticipation of a digression below, however, the criterion of time should not be used as a definitive characteristic to differentiate between educational and instructional video.

Report

In the field of moving images, this concept is primarily associated with television news programs (Kamp 2017, 146): In just a few minutes, a process, a fact, is to be explored in depth. The following structure, which is also used in newspapers, lends itself to this: First, the event is described. Then it is explained how it came about, the consequences are named and finally the result is evaluated. (Kamp 2017: 146)

“Evaluation” already says it all: the author appears here, he or she strives for objectivity, as it were (Kamp 2017: 146). The intention is a certain authenticity or evidentiary function — he, she, div. is “just” there. Moreover: The report is not only related to the newspaper article, but also to a cinematic strategy, the hook: after an overview, informative, even captivating introduction, details follow.

Reportage

Reportages are characterized by a more obvious, namely narrative note, insofar as they are intended to encourage the audience to experience them in the course of an authentic description. The distance between the journalist and what is shown is less than in a report. The “documenting” persons are sometimes even integrated into the events, even suffering with them or trying out what has been done in front of the camera. This presence is emphasized by the reporter appearing visually more often, making personal statements and comments. (Kamp 2017: 148)

Tip

On the one hand, it is generally advisable to have the presenter appear in the picture “every now and then” / have them appear in front of the camera due to the effectiveness of the “human medium”, at least for longer instructional and explanatory videos. This can promote the bond between the presenter and the audience and thus also the communication of any content (≈ personalization principle). To emphasize the “can”, it should also be mentioned that the research situation on the appearance of speakers is ambiguous — we will come back to this in the third part of this blog post. In any case, and as a possible side effect: loosening up and structuring are possible (with longer videos). In the case of short films aimed at instructions, a “personal” appearance can be dispensed with (≈ coherence principle).

Documentations

Documentaries are more analytical than reports and documentaries. In them, the author’s personal distance from the subject matter dealt with in the film is particularly emphasized. Opinions tend to be taboo in documentaries. The second criterion for the definition of a documentary is the time difference between the broadcast/production and the subject matter of the documentary. The documentary can or should therefore offer a certain degree of completeness while providing an overview. (Kamp 2017: 148 f.) So-called educational films are considered documentary and should be a maximum of 15 minutes long (Harder n.d.: 103), although the conceptual blurring, the synonymous use of “film” and “video”, should be considered here.

Interviews

This format initially describes a means to an end and an element that rarely stands on its own or is used in the context of other moving images: For example, interviews can be part of documentaries or reports in order to allow those involved to have their say. They thus offer proximity, can substantiate statements by witnesses, and can promote a loosening, attention-grabbing rhythm. A stand-alone interview, which can be accessed via a learning platform, for example, should have a demonstrative note — in the sense of Persike’s (2019: 5) explanations. It could therefore also be assigned to the “+1”, the third format category we have defined.

Tutorials

To the point, straightforward — that’s how this type can be described at first glance. These classics are videos that explain the function of software as a whole or just one aspect of it. They are relatively short, often only a few minutes long. Tutorials can therefore certainly be associated with the term “nugget”, which is not only used for moving media teaching units, as a description of a short teaching unit.

These videos often do not stand on their own — especially in the case of software training. They can therefore be integrated into a help section of a website, as part of a series, so to speak. Music is often even omitted here. In order to get to the point quickly, a screencast (see below) and narrator text are started immediately after a short title bar. Screencasts of software to provide an insight into a program to be learned are the characteristic feature of a tutorial (Harder n.d.: 103).

At second glance, but still quite short, onboarding videos must be understood as tutorials — to introduce new employees or to get them in the mood for a course. However, such videos can be realized more elaborately — with music, animations, i.e. far beyond a screencast. These steps even make sense if the video is intended to promote your course series and potentially retain learners. Such and also longer tutorials, even in connection with a series of several lessons, can start with a teaser (also known as a hook, cold open) to introduce and captivate for the subsequent, longer content. In the course of a series of videos, a recap (the recapitulation of previous steps/units/videos) can or should even be included in order to reactive existing knowledge on the part of learners to compensate for an interval between the units and/or the appearance of the videos. Depending on the form of delivery (via common platforms or via an HP5 plugin), chapter markers can be set so that a recap can be skipped. This can be useful if the previous video has just been viewed and/or previous content is still present.

Longer tutorials (or generally stand-alone documentaries, reports, etc.) can and should have a more elaborate and therefore longer intro that favors or at least reflects the mood of the series, course, etc. This intro marks not only a specific video, but can also mark a series of videos. This intro not only marks a specific video, but can also mark a series of videos: It sets the mood for the upcoming style of the video, the series or entire series of events, even the person teaching it, offers recognition and thus creates a connection to other units and the same “label”. This can encourage the learner to stick with the course, but can also serve as a guide.

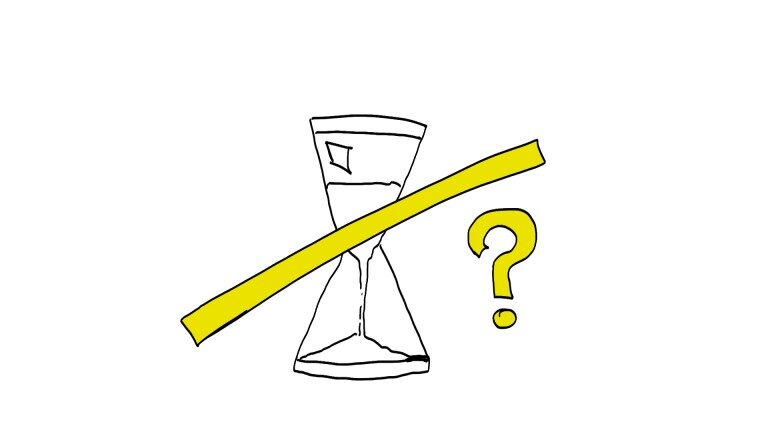

Can educational videos really be categorized by duration? With regard to the definitions of different formats: rather not …

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC BY 4.0

Excursus: How long is too long? The length of teaching and learning videos

It should be noted that it makes little sense to define teaching and learning videos solely by their duration (Persike 2019: 10). As has probably already been indicated, there are far too many variants and mixed forms between different formats and methods, not to mention usage situations. Nevertheless, we would like to discuss a common “rule” regarding the length of videos: The so-called 6‑minute rule suggests that once the sixth minute begins, learners’ attention wanes or the video is less likely to be viewed further.

As with many rules of thumb, this should only be considered in context. The rule itself applies above all in the context of MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) (Johanes/Lagerstrom/Ponsukcharoen 2015: 15), i.e. large-scale events that regularly aim to or should address a correspondingly large audience (Ebner/Schön 2017: 4; Persike 2019: 2). There has already been a “downward correction” in this respect: Thus, the original maximum of 10 minutes has become said 6 minutes (Johanes/Lagerstrom/Ponsukcharoen 2015: 2). However, a range of 1 to 20 minutes can be found for educational and explanatory videos (Harder n.d.: 103. and Ebner/Schön 2017: 3). And as we have seen, the formats within the overall complex are defined as being “so and so” long here and different there. However, it can be helpful to apply the six-minute rule to the subdivision(segmentation principle) of a video into content units (Guo/Kim/Rubin 2014: 4) in order to promote chunking, i.e. the handling of information by the learner’s brain.

Overall, a distinction should be made on a case-by-case basis: A missed lecture is certainly longer as a video than a crisp explanatory video, as has already been indicated. And such a video, even if longer, is probably better than having just missed the lecture. Similarly, the first part of this article on teaching and learning videos already pointed out that form and content are inextricably linked. Consequently, a longer video can also be successful because it may be able to hold the students’ interest or win it back again and again. Conversely, not every subject matter can be presented and/or condensed in an infinitely attractive way — this could be described as a “reduction trap”, more on this in the third part of this series of articles.

In addition, and in line with constructivist learning theory, the individual or the learners themselves must be taken into account ≈ each learner gradually creates an individual, conditionally conscious construction of an equally individual view of the world. Accordingly, learning is also based on a foundation of subjective experiences, values, beliefs, orientations and patterns. Therefore, on the one hand, a kind of target group analysis is useful on the part of the person producing the video in order to better reach learners. On the other hand, interests (in a video on the part of learners) must always be understood in the context of the individual world view and such an interest as an individual achievement.

The assumption that the length of a video is context-dependent can also be underlined by a study from Stanford University: It concludes that the aforementioned rule should not be taken too literally, students definitely also watch longer videos (Johanes/Lagerstrom/Ponsukcharoen 2015: 15 f.). Importantly, the study points out that videos [apart from any livestreams] are often (can be) viewed several times by learners (Johanes/Lagerstrom/Ponsukcharoen 2015: 15 f.).

The overall conclusion is this: A video should be as short as possible, but also as long as necessary.

+ 1 — Demonstration videos

Demonstration videos rarely stand alone, but are viewed in context. This can be of a non-moving-media nature ≈ a clickable interview in the learning management system alongside any texts. Then demonstration videos can be used within other videos, namely explanatory videos — as an integrated interview, for example. Characteristic of demonstration videos, when they stand on their own, is that they are without commentary, have no narrator text and their communicative-didactic and aesthetic presentation is little or not at all developed — because they should not or do not have to stand for themselves. They lack an autonomous “explanatory character” (Persike 2019: 4).

Demonstration videos may well have been produced for a specific occasion — for example, to serve as illustrative material for examining behaviors in order to enable students to see the behaviors discussed. The term demonstration material can then be used to describe any material that is integrated into a teaching concept and, in turn, a teaching and learning video, analogous to the interview in question. It can therefore also be excerpts from other films, news programs, etc. (Persike 2019: 4)

Film offers a special potential in this respect — similar to the invention of microscopy: the microscope made the microcosm accessible or visible. Of course, a film can depict events there in time or capture them with the help of highly magnifying lenses. In addition, the moving image can also make time “visible”: time-lapse photography can make changes visible that regularly escape our attention because they only happen slowly. Conversely, movements can be made visible that we cannot grasp because they happen too quickly for our perception.

As with ping-pong: the two sides of the coin are connected — in variable forms. We are now changing our perspective and turning our attention to the second side of the field of teaching and learning videos.

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC BY 4.0

Page 2: Processes and means of production

This side of the coin in the field of teaching and learning videos is — it should be emphasized — not in contradiction to the first, but complements the teaching and learning video formats mentioned there with a technical-economic view that captures the realization — visually similar to a ping-pong game. For the sake of clarity, the field of means of production is divided into two areas: Technology and process on the one hand and quality of execution, circumstances of realization on the other.

The second page in the field of teaching and learning videos in focus

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC BY 4.0

Techniques

Live action footage or real footage

It should be mentioned for the sake of completeness, because we have of course already talked about formats that are often enough associated with real images — such as the reportage or the report: Firstly and fundamentally, the production of a film can be divided into real footage or live action footage on the one hand and animations or abstractions etc. on the other. In the first case, a real camera is used to capture an equally real world. In the second case, for example, virtual cameras can be used as part of 3D software. The movement over aspects shown on slides as part of a slidecast, as an enlargement or as a slide transition, can be understood in a similar way to a virtual camera.

The introductory subjunctive hints at this: In the wake of increasingly realistic animations and computer-generated images that are barely distinguishable from reality, the difference between “animations here” and “real image there” is primarily a theoretical one. Moreover, even without a Hollywood production budget, real footage in front of a green screen can be combined with virtual worlds or animations at home. Nevertheless, the distinction is likely to have a lasting effect in the production of a video — because a real camera may or may not be required. However, a film realized with layering technology can be captured with a real camera on the one hand and be considered animation on the other.

Screencasts/Slidecasts

Screencasts are screen recordings. They are particularly suitable when it comes to shorter and instructive teaching content — software training or instructions. The production method is associated with the term tutorials (for example: Harder n.d.: 103). The running time of such tutorials is usually less than 10 minutes (Harder n.d.: 103), even though we have already seen that time should not be the measure for classifying teaching and learning videos.

Slidecasts, on the other hand, are often purely visual recordings of a presentation in the context of standard presentation software, which may be accompanied and/or supplemented by speaker text. Without a real camera, the presentation content is recorded as a video.

Not only can videos be of this nature as a whole, such material can of course also be integrated into other videos: For example, the person speaking could be added picture in picture on the slides or switched back and forth between slides and the person speaking (in a varied manner) using a video editing program. It is even possible to introduce animations for transitions that can be described as separators (/stingers etc.), which give the change from slide to person a clear and structured expression. However, no static image of the person giving the lecture should “simply” be placed permanently next to the slides — such a measure can have a demonstrably alienating effect (coherence principle).

The term micro-lecture is also based on a slidecast (Harder n.d.: 103). Such videos should be a maximum of eight minutes long (Harder n.d.: 103). Not only the mico-lecture (Harder n.d.: 103), but also slidecasts in general are characterized by the fact that they are relatively easy to realize. With the (often familiar) presentation software and microphones already installed in many computers, a result can be achieved quickly — a presentation can become a movie. At the same time, any animations that can be called up in the software can help to draw attention to certain aspects depicted on the slides used (Harder n.d.: 103) — provided that these animations are used in moderation.

However, both the quality of the sound due to built-in microphones and the moving media capabilities of presentation software must be classified as limited in view of the possible demands of learners. In addition and in any case, the field of presentation slides must be classified between efficiency and communicative-didactic “pitfalls”: Slides often end up being too text-heavy (Karia 2015: 39 ff.) — not least due to an effort to achieve efficiency: post-use as a handout. At least in the case of slidecasts, a compromise should be found in this respect.

Laying technique / animations

The laying technique can be regarded as a traditional animation principle, as it can be used to create the impression of movement or at least a context from individual images. Consequently, the laying technique is also a way for people who are not technically or software-savvy to visualize facts: For example, cut-outs, printed or written texts etc. can be moved step by step and photographed. Cut-outs, printed, written text, etc. could be moved and photographed step by step to create an animation. This can be realized with common smartphones in high quality — as a photo sequence.

Then the process of moving could also be filmed (again via smartphone) without interruption. Or something could even be painted, drawn or written in front of the video camera. In the case of a video recording, the person writing can comment directly on what is shown so that no further editing is necessary. (Where coordination and presentation quality are likely to be a challenge.) The real hands of the person producing the video are regularly visible and probably characterize this process.

In addition to photography or filming, real hands from third parties or graphic hands (as part of a graphic template) can also be used in a second step during post-processing. Many software solutions offer ready-made hands (Aldrian 2019: 4 and 8) — but licensing issues must be checked in this regard. This applies all the more — without wanting or being able to provide legal advice — if the aim is to publish the final videos beyond §60a UrhG (teaching and learning) or if the material is released for others to use and edit in the sense of Open Educational Resources (OER). The extent to which (design) templates and the graphics provided by a software provider may be openly licensed and thus incorporated into open formats, i.e. formats that can be used by other users, must be clarified in advance. Twillo offers initial assistance with regard to legal aspects.

In addition to analogue animation technology, various software solutions offer the possibility of creating digital animations in 2D to 3D. Compared to the “jerky” and or deliberately “handcrafted” laying technique, these allow far more dynamic, flowing visualizations with a realistic effect to be created. However, they are often more costly and/or time-consuming to use. Software solutions that use graphic templates to create an animation must be checked with regard to their license conditions.

Interactive videos

On the one hand, interactive videos are another form of production; at the same time, they can be a variation of the other types. In addition to the reception of an audiovisual image and sound sequence, they offer the possibility of integrating a higher degree of activity, namely interactivity. H5P content can be integrated into many learning management systems and website content management systems using plug-ins, allowing videos to be enriched with quiz units and additional information. This allows the knowledge presented in the instructional video to be deepened and, if necessary, consolidated (≈ activity principle) — either within a teaching-learning environment or even publicly on a website. Interactive videos are also said to have the potential to encourage students to stick with a topic or, more specifically, a video (Aldrian 2019: 6).

However, H5P editors can also be used to add chapter markers so that it is easier to stick with the video as a whole if passages are repetitive or familiar to learners. Such sections can therefore be skipped. Chapter markers can also be set relatively easily on many video platforms.

However, the careless placement of interactive or inserted components that go beyond chapter markers in existing materials or videos can run the risk of having a confusing or disruptive effect on learners — for example, because music is abruptly stopped by a quiz. Ideally, interactivity should be placed at points that make sense in terms of content, formal design and didactic communication: at the end of a chunk or topic block, at the end of a chapter, etc. If necessary, suitable places can already be planned during the conception and production of a video. The music could fade out there to facilitate the transition to the quiz, etc. Conversely, the use of the same video away from interactive content can be restricted.

Virtual realities: 360° videos and augmented reality

360° videos can be divided into fully spherical (360° x 360°) and semi-spherical films (360° x 180°, also known as FullDome — for hemispherical projection sites such as modern planetariums or media domes). Computer-generated, three-dimensional worlds can be created and viewed. It is also possible to capture real events in 360° (live action footage) in a similar way to conventional cameras.

Until a few years ago, these films were captured using extreme fisheye lenses and/or by using multiple cameras. The image sequences from several cameras were stitched together using software (≈ stitching). Today, there are corresponding (action) cameras with wide-angle lenses and or multiple lenses that can automatically output fully or semi-spherical films.

These films can be viewed using glasses systems ≈ virtual reality. Alternatively, (prefabricated or self-made) cardboard or similar can be used as mounts for smartphones to avoid the cost factor of VR glasses. If necessary, these films can also be viewed “flat”, in the browser window and by mouse.

360° videos offer the potential to gain new perspectives — such as those that cannot be achieved in reality due to dangers or for economic reasons. This provides the opportunity to immerse yourself in unknown, new, microscopic, etc. worlds. This primarily refers to a real spatial, illusory immersion (in contrast to a general immersion as immersion in the world of a book, for example ≈ Hahn (2018)). It is interesting to note that 360° videos partially turn their audience into co-creators; he/she/they themselves choose the view of what is happening (Hahn 2013: 146), rather than having it completely predetermined.

It is worth noting that, as is always the case, the appropriateness or usefulness of a 360° video must be weighed up so that the use of such a video does not become counterproductive. The actual opportunity to look around freely is a major challenge from a design perspective in order to convey facts in an understandable way (Hahn 2013) — because there is no single focus area.

The terms augmented reality and mixed reality are used to describe the interweaving of reality and virtual worlds (Persike 2019: 8 f.). The experiences made possible by this go beyond the “usual” interweaving of the viewer’s space and what is happening on the screen as an immersive immersion in the actually flat world of the screen, as a shared excitement with a story: In concrete terms, this also refers to initially invisible facts that supposedly become visible by looking through the respective devices, for example via glasses systems or using the smartphone camera and the screens there. The numerous sensors, the gyroscopes, of smartphones are used to locate virtual objects in the real world using apps, to place them in a “fixed” position — despite the devices being held in the hand.

The realization of such projects is — as the components mentioned above show — still complex. In contrast, 360° videos already have a consumer-ready level and corresponding workflows as described.

For the sake of completeness, a semi-digital version of augmented reality should also be mentioned: for example, in the form of a video walk. Using only an iPod or similar device and the acoustic and visual information it makes possible as still images, but on video, learners can be guided through a real environment and experience different times, worlds and situations more or less superimposed on the actual space during the walk via headphones and screen. An example of this is the “Alter Bahnhof Video Walk” by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller for Documenta 13.

In fact, there is a third side to the coin of teaching and learning videos: Techniques and circumstances for realizing a video … a look behind the scenes, so to speak

Image by Sönke Hahn based on Sarah Brockmann, released under CC 0 (1.0)

Quality of execution, circumstances of realization

High production values: content pre-produced or streamed in the studio

The decisive criterion for this form of production is the explicit concept for a video, a corresponding realization and a professional level of production. It is no coincidence that such educational videos are referred to as “blockbusters” (Ebner/Schön 2017: 7), as they can basically be staged in a similar way to big Hollywood films and prepare content in a correspondingly elaborate way. However, Hollywood has become more and more feasible “from home” in recent decades thanks to various apps and automated processes, although this is still not without effort, resources and skills.

High production values can be transferred to any cinematic material, with little overlap in terms of the craftsmanship, technical and aesthetic quality of animations, live or pre-produced real footage: while the laying technique may be a simple process on the one hand, it can also be realized / associated with great effort for aesthetic or didactic reasons: The manual, simple charm of the laying technique could function as a visible abstraction in order to achieve a new approach to the topic. If necessary, color-corrected images in a certain look that underlines the mood, which may visibly differentiate between different time levels treated in the film, and with animated cross-fades in the form of callouts with additional information, for example, enrich the material …

In order to achieve a high standard, a professional camera or even several cameras, appropriate lighting (e.g. three-point light) and an image mixer can be used; a background system can be used so that any existing private space (≈ home office) becomes invisible, and the corporate design of an institution can be used for a uniform external image. Despite the effort involved, a teleprompter can make things easier, so that the script can be read more easily (even if it is trained and not too obvious). At the same time, eye contact with the virtual audience can be facilitated (personalization principle).

If the live streaming is recorded or “only” pre-produced, the effort and resource requirements sometimes differ: If details of something you want to show in the studio are to be shown in the live stream, an automated camera or a person operating the camera or another camera controlled by an image mixer would be required: Zoom in on something, a different angle of something on your desk. The recorded material of a live event can be supplemented with post-produced material if the resources mentioned are not available, but the aim is to use the video in a time-sensitive manner and make it available on demand. In post-production, other camera settings can then be added so that what is discussed in the video file (didactically useful) is more clearly visible compared to the live stream. Mistakes and lengths in the live lecture can now be removed. A purely pre-produced video makes it possible to create the impression of a great deal of effort in the sense of non-linear editing with just one camera: different settings can be selected one after the other and combined in the editing program. Caution: Although live streaming of a recording is possible, the potentially interactive component, i.e. being able to respond to questions live, is sacrificed.

Here are a few more tips on the use of green screens. Recording/streaming yourself or the speaker in front of a green screen allows you to integrate individual backgrounds — whether it’s just to hide the home office situation or to avoid having to build a backdrop. Materials that match the topic or, as mentioned, a logo can be integrated as virtual backgrounds.

The use of a green screen can also make it possible to combine the speaker with the slidecast without a specific frame. In this way, the quasi-cut-out silhouette can be visible in parallel with the slides or on the slides. Care should be taken to ensure that essential content is not covered up. This procedure is an alternative to a split-screen method, in which neither the slides nor the speaker are displayed to fill the format. Changing these settings can even be done “solo” using an image mixer.

(The function of many popular video conferencing software packages proves to be a compromise in terms of production effort: There, virtual backgrounds can be selected under effects. These backgrounds range from blurring the real background to selecting prefabricated backgrounds or backgrounds created by users. These materials can then be designed in a recognizable corporate design for the sake of consistency. Caution: Although these processes do not require a green screen in the background, the human being is recognized as such with software support and virtually cut out. However, this cutting out has so far or often only been successful to a limited extent. Gestures or objects in the hand can sometimes also be filtered out — sometimes to the detriment of the intended presentation).

Overall, this brief list should have made it clear that, on the one hand, this is a complex undertaking — technology, software, number of people involved. On the other hand, and as already mentioned, at least some professionalized competencies or recourse to external forces may be necessary.

Filming — “Two to three birds with one stone”: Presence and/or live stream and/or archivable video file

We already touched on this approach when we looked at the first side of the coin in the field of teaching and learning videos, with regard to authors and their intentions: It is undoubtedly practical to generate material that can be used in the long term by filming a face-to-face event. As a form of hybrid teaching (understood here as a spatial hybrid, presence and virtual, with an identical teaching situation ≈ live), an audience on site as well as a connected audience can be reached via stream.

Certainly in the context of the pandemic, one could add “better this way than not at all”. However, we have already seen above that there are stumbling blocks here: The event possibly captured from the back of the room with a single camera may lose its impact on the video, slides are not ideally legible. Basically, there are different media. So if there is a comprehensible, efficient intention to kill two (with live/hybrid: three) birds with one stone, then a higher technical and time expenditure is recommended. On the one hand, this can promote learning through better readability and accessibility. On the other hand, the effect of a teaching and learning video can be enhanced in terms of aesthetic added value and growing expectations on the part of the audience (we will come back to this in the third part of this blog series). Specifically, this means the use of two to three cameras and/or cameras with auto tracking/panning/zoom functions that can be controlled by gesture. At the same time, projected slides should also be offered to the virtual audience as split-screen content via video conferencing software. It may be necessary to edit the material afterwards or use live image mixers, feed in wireless microphones etc. in order to do justice to the “other” medium (≈ reception situation).

Outsourcing between facilitation for teachers and competence gain for learners

The production of any videos can be outsourced — agencies can provide support here, where possible didactic centers (at a university) can help or the tasks can be handed over to student assistants or students. In the latter case, there is the didactic potential to realize learning-through-teaching by means of video production (Ebner/Schön 2017: 4; Persike 2019: 22). This means that the production of videos can be assigned to students as a task — as project work, for example. On the one hand, students dedicate themselves to a specific topic and convey something to their fellow students. On the other hand, they can hone their media skills, specifically in relation to film, as part of the side course.

However, when assigning the video production to students, both to assistants and to course participants, the ease for teachers varies: Students participating in the course may need to be supported in terms of design, technical and software skills. In the case of student assistants, in addition to the relevant qualifications, consideration must be given to whether software and technology is available to the assistants in a suitable form or whether it can be provided.

Conclusion

We have related various formats of teaching and learning videos to equally diverse, not least technical and economic processes. This has resulted in a field of tension of possibilities. Intentions and techniques can be combined. The spectrum of possible uses for teaching and learning videos, as well as the situations and circumstances in which they can be used, is so wide that it is not possible to define teaching and learning videos, and perhaps they should not exist. Such pigeonholing would ultimately obscure the potential to address specific topics and concerns via video — through a combination.

However, this second part should have indicated that although teachers can draw on an equally wide range of possibilities, they should reflect on didactic-communicative considerations, budget and time issues, their own and the learners’ skills at an early stage. Therefore, in the next part, we will take a detailed and summarizing look at the communicative-didactic potential of teaching and learning videos. We will also take a critical look at the use of educational videos. The next article will be published on May 28, 2022.

If you missed the first part or would like to continue with the third part of our series on teaching and learning videos:

- Part I: Characteristics and didactics of instructional videos

- Part III: Potential and criticism

About the authors

Franziska Bock, M. A. and Dr. Sönke Hahn are research associates of the project “OER-Portal Niedersachsen”: twillo — Lehre teilen. Bock is active in the field of university didactics and deals with questions of writing didactics and the conception of reusable teaching and learning materials. Hahn is an interdisciplinary scientist, filmmaker with international performances and multiple award-winning designer. As part of the Emden/Leer University of Applied Sciences, Bock and Hahn see it as their mission to go beyond good content to advance teaching as such.

References

Aldrian, S. (2019): Teaching video. Center for University Didactics. University of Applied Sciences of Business, Graz. URL: https://www.campus02.at/hochschuldidaktik/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2019/09/Lehrvideo.pdf (retrieved on 15.03.2022).

Ebner, M. / Schön, (2017): Learning and teaching videos: Design, production, use. E‑learning handbook. 71st supplement (October 2017). 4.61. S. 1–14.

Guo, P. J. / Kim, J. / Rubin, R (2014): “How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos” In: L@S 2014, March 4–5, 2014, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Hahn, S. (2013): “Fulldome vs 16:9. On the differences in the conception, design and production of a feature film in the dome and in the classic picture format using the example of the film versions of breakFAST” In: Institut für immersive Medien der FH Kiel (ed.): Jahrbuch immersiver Medien 2013. Schüren: Kiel/Marburg, 133–147.

Hahn, S. (2018): The sixfold nature of immersion: an attempt to (discursively) define a multi-layered concept URL: https://www.academia.edu/35937976/Die_Sechsfalt_der_Immersion_Versuch_der_diskursiven_Definition_eines_vielschichtigen_Konzepts (15.03.2022).

Harder, S. (n.d.): Teaching videos. Possible uses in part-time studies. URL: https://www.uni-rostock.de/storages/uni-rostock/UniHome/Weiterbildung/KOSMOS/Lehrvideos.pdf (retrieved on 15.03.2022).

Johanes, P / Lagerstrom, L. / Ponsukcharoen, U. (2015): “The Myth of the Six-Minute Rule: Student Engagement with Online Videos” In: 2015 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition.

Kamp, W. (2017): AV media design. Europa Lehrmittel: Haan-Gruiten.

Karia, Akash (2015): How to design ted worthy presentation slides. Akash Karia, op. cit.

Merkt, M. / Schwan, S. (2018): “Learning with moving images: Videos and animations” In: Niegemann, H. / Weinberger, A. (eds.): Learning with educational technologies.

Persike, M. (2019): “Videos in teaching: effects and side effects” In: Niegemann, H. & Weinberger, A. (eds.): Learning with educational technologies. Springer: Germany.

Rosenbaum, L. (2018): “Youtube — Developing educational videos into an interactive learning experience” In: Blog E‑Learning Zentrum Hochschule für Wissenschaft und Recht Berlin. URL: https://blog.hwr-berlin.de/elerner/youtube-lernvideos-zu-einem-interaktiven-lernerlebnis-weiterentwickeln/ (accessed on 15.03.2022).

This article by Franziska Bock and Sönke Hahn is licensed under CC BY 4.0 unless otherwise stated in individual content.