The terms in the field of teaching and learning videos are as numerous as they are difficult to distinguish from one another: Probably analogous to the albeit “asymmetrical” (Meyer 2018: 133) connection between teaching and learning, the terms educational video and instructional video are used synonymously (for example: Ebner/Schön 2017). An educational film, on the other hand, is a documentary format of a maximum length of 15 minutes that is realized with high production costs (Harder n.d.: 103). This distinction is probably already problematic with regard to the now synonymous use of the terms film and video. Educational videos are then equated with explanatory videos (Persike 2019).

It is characteristic of explanatory videos that they have an entertaining touch. This is achieved through narration and comic-style visualization, among other things. Explainer videos should be differentiated from tutorials, which are shorter and therefore less entertaining. This is because tutorials are primarily determined by a screen recording (screencast). (Harder n.d.: 103) Nevertheless, a look at the range of tutorials on a platform such as YouTube should show that this distinction is hardly ever implemented.

Explanatory videos are likely to be understood as more instructive and concrete than the recording of a lecture. After all, explanatory videos are dedicated to condensed, small-scale aspects compared to a lecture recorded on video, for example. Consequently, explanatory videos are shorter in duration. A lecture, on the other hand, is more expansive in nature, meaning that the running time of such a recording can easily be well over an hour. A synonym for the recording of a lecture in the lecture hall can be the term “presence recording” (Harder n.d.: 103).

The term “digital lecture” is used to describe both explanatory videos and educational videos (Persike 2019: 4). The “live digitized lecture” (Persike 2019: 4) is a sub-item of the digital lecture and refers to the recording of a face-to-face event.

Speaking of “live”: While the terms video and film may give the impression of an archivable file, in the context of teaching and learning videos, the (simultaneous) live streaming of a lecture could be mentioned in addition to a recording of a live event. The simultaneous streaming of a live event held in front of a face-to-face audience and learners connected virtually is sometimes referred to as “hybrid teaching”. (For the definitional diversity of the term “hybrid teaching”, see Reinmann 2021).

An e‑lecture, on the other hand, is a lecture produced in advance: Compared to the recording of a face-to-face event, such videos are shorter and of higher quality, even realized in the studio (Harder n.d.: 103). In addition, the content of an e‑lecture is more detailed than that of a traditional lecture. This is because it is dedicated to individual aspects. (Persike 2019: 5)

Demonstration videos are those films that are used in teaching but have no “explanatory character” (Persike 2019: 4). Consequently, even if this video material was produced specifically for teaching purposes, it may have no narrative text and little narrative preparation. Furthermore, demonstration videos can also be excerpts from other forms of moving media. (Persike 2019: 5) In this context, one could therefore speak of illustrative material.

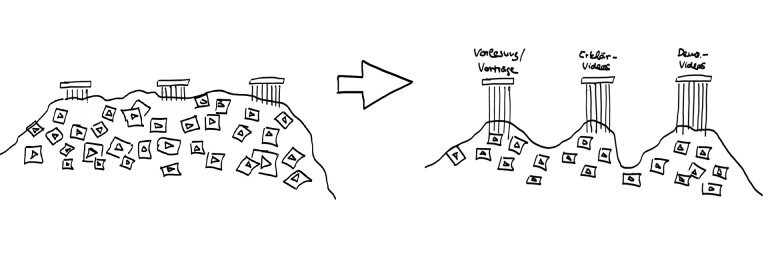

Attempt: To give the formats of teaching and learning videos a little sharpness ...

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC 0 (1.0)

Overall, the intention of what the video should achieve and the form of realization of the video as well as production values are summarized in a less differentiated way to describe the complex of teaching and learning videos (e.g. Persike 2019).

Overall, on the side of a concern associated with videos, basic trends or format categories can be recognized within the complex of teaching and learning videos 2 + 1: the lecture captured on film and/or transmitted by video, correspondingly captured lectures etc. as well as explanatory videos. The additive “+1” refers to demonstration videos according to Persike (2019: 5) — i.e. the aforementioned illustrative material. As already mentioned, this tends to be classified as a means to an end.

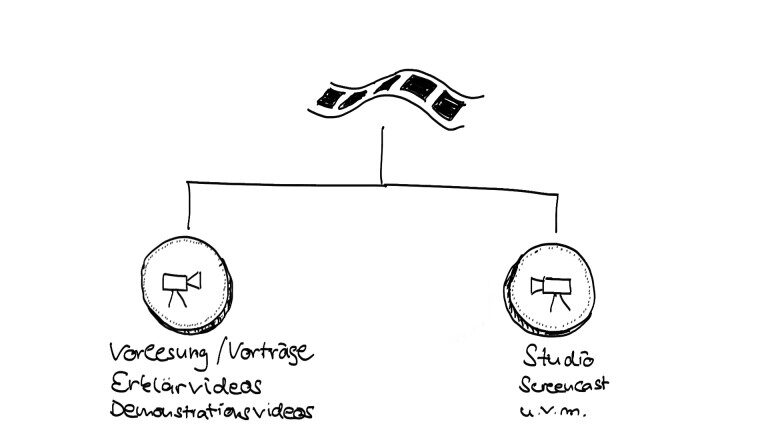

These 2 + 1 format categories can be related to different forms of video production and realization. We have already got to know some of them: screencast, award in the studio, animations. A field of tension emerges. Metaphorically, we could speak of two sides of the same coin:

Two sides of the same coin: A field of tension between formats and processes (more on this in part 2 of the series)

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC BY 4.0

Before these two poles, the format or intention side on the one hand and the production side on the other, can be examined more closely and the types occurring in this field can be defined more precisely, a basic definition of teaching and learning videos must be provided.

Four characteristics of teaching and learning videos

Four characteristics can be identified for the overall complex of “teaching and learning videos”. However, due to the ubiquitous convergence (Hickethier 2007: 1 and 11; Burkhard 2019: 36 ff.) of different media, the characteristics cannot always be assigned exclusively to teaching and learning videos:

- Audiovisualization (- multimedia, “moving image”): Targeted content is audiovisualized — in line with the medium of film and its regular combination of sound and visual presentations. In this context, one could also speak of multimedia. For the medium of film is to be understood as a combination of several “basic media” (Schanze 2002: 219 f.) — sound, image, text, etc. (Whereby it must be added, again restrictively and for the sake of completeness, that these basic media need not be the smallest unit of a work. For each image can itself also consist of various signs and meta-medial facets). In view of this characteristic of the medium, it is worth taking a look at the didactically and communicatively insightful multimedia principles (Mayer 2021) and their theoretical background when designing educational videos. These principles are not exclusively dedicated to the moving image. Nevertheless, these principles can provide orientation when designing a film. This is because an educational video that follows the principles can promote a multi-channel utilization of the working memory that is conducive to learning. In addition, the fascination with and increased focus on the moving image mentioned at the beginning of this article is worth taking up. This is because films are a trend, a familiar communication situation for learners, so to speak: This threshold in the exchange with learners can therefore be taken “once already”. Moreover, due to their dynamic nature, videos are also suitable for demonstrating and explaining dynamic facts (Harder n.d.: 103).

- Potentially location-independent use: The files and videos can be viewed “from anywhere” and the intended content can be learned at any time. “Potentially” means: depending on the provision (internet or intranet or password-protected learning platform etc.), end devices (FullHD, possibly UHD/4k capable) and internet access (data volume, transmission rate) of teachers and learners.

- Potentially “asynchronous” (Ebner/Schön 2017: 2) provision: teaching and learning videos as files can be called up, stopped, rewound and viewed again in the event of missed events, time-sensitive learning organization and/or in the sense of an individual learning pace for deepening, for reviewing (Rosenbaum 2018: n.p.). “Potentially” means here: This characteristic does not apply if it is exclusively a live transmission.

- Didactically weighed up, classified, designed & realized: In the sense of an educational concern, the concepts for any videos or the videographic preparation of an intended content should follow didactic considerations (Ebner/Schön 2017: 2). In addition, a video can or should be integrated into larger didactic contexts — such as a teaching concept (Aldrian 2019: 3).

A didactic touch is indispensable

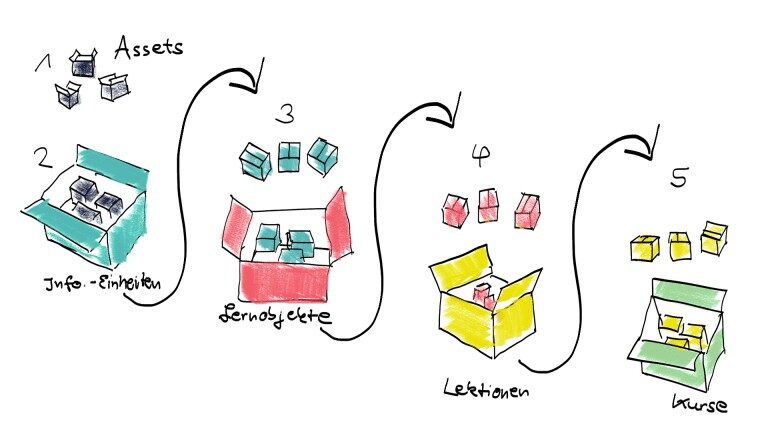

Before we can look specifically at the various formats of teaching and learning videos, we need to take a didactic perspective. After all, didactics is the study of teaching and learning (Jank/Meyer 2020: 14). It should therefore be able to answer fundamental questions about the use of videos in teaching. Therefore, it must first be noted: Both the use of instructional and explanatory videos and the concrete design of the same should be carried out with didactic considerations in mind. Experience has shown that didactics is met with skepticism. Perhaps it sounds too much like school. A communicative-media approach is therefore an alternative: The what, an intended content and the how, the narrative style and concrete audiovisual design of said content, always and in practice result in an inseparable connection. It is well known that good content can be poorly communicated. And an illustration does not help if it shows “nothing”. Media within a film and within a course are never just mere tools like those of a workbench. Rather, they are part of the context. And at the same time, a possible course and the potentially shared space created together with students are media as a whole. We are all too familiar with the tension between the need for completeness and simplification in teaching planning and this also applies to the planning of teaching and learning videos. The term didactic reduction refers to the preparation of material for the learning group for whom the content is to be made comprehensible and accessible. Abstraction and participation (Lehner 2020: 145) are just two possible forms of didactic reduction. The challenge always lies in selecting teaching and learning material on the one hand and thus limiting explanations to the essentials. On the other hand, didactic reduction is achieved by reducing a subject matter at the content level. The technical complexity is maintained, but the abstract statements of the reduction are illustrated by means of aids — e.g. by means of presentation, demonstration and proof strategies (Lehner 2020: 14). However, highly abstract presentations or over-simplification can run the risk of reducing learning success, as either “the material […] is simply not seen as a challenge” (Ebner/Schön 2017: 7). Or, if oversimplifications result in technical and factual errors, this can lead to misinterpretations by learners. We will take a closer look at this challenge in the third part of this blog series. With regard to the didactically and/or communicatively-medially motivated use of teaching and learning videos, one could speak of granularity. This is because adopting a corresponding perspective is not only useful for a single video: on the one hand, a video should itself be designed in line with didactic recommendations. On the other hand, it is also about the didactic and content-related fit of the teaching and learning videos into an overarching overall concept or teaching concept (Aldrian 2019: 3). A video is therefore not used for its own sake, but fulfills a purpose. An instructional or explanatory video “rarely stands alone” (Aldrian 2019: 3). So the question must also be asked: is the medium, the format, suitable for illustrating these facts? As already mentioned, the dynamic sequence of a video is certainly particularly suitable for audiovisualizing processes. The multimedia principles of the American psychologist Mayer, for example, which also apply beyond the moving image, can provide orientation for the concrete design, the balancing of image and text — more on the principles in a moment. However, granularity does not only mean the placement of the teaching and learning video within the overall context of a semester course. On the media-didactic and media-technical side, it also means a description of the video material. Teaching and learning materials can generally be classified in terms of size and didactic content. Teaching and learning videos can also have different granularities and thus different didactic-structured complexities. With regard to reusable learning objects, which also include teaching and learning videos, the Austrian sociologist Peter Baumgartner refers to a Matryoshka-like principle when he conceptualizes five different levels of granularity for teaching and learning materials. The so-called media objects (assets) form the first level on the granularity scale. According to Baumgartner, text, images and sound are the smallest units in terms of the aforementioned levels. These media objects can be combined into “content-structured information units” and thus reach the second level of granularity. It goes on to say that “only when these information units are didactically motivated and convey or help to develop a specific learning objective does a learning object emerge from them” (Baumgartner 2004: 317). This Matroschka principle comprises two further stages, provided that teaching units and courses are regarded as reusable teaching and learning materials: “In accordance with the didactic requirements […] appropriately adapted lessons and courses are generated through a specific combination of learning objects.” (Baumgartner 2004: 318) If units, lessons or courses are designed and realized as teaching and learning videos, for example, they can be located at several levels of granularity. Depending on their orientation, enrichment and seriality, they are either information objects or learning objects or more didactically complex entities: units/lessons or courses. By the way, if you are looking for templates to build entire courses, then twillo support — using course templates that can be integrated into learning management systems for inverted classroom, problem-based and research-based learning.

Films in the context of “larger” teaching-learning contexts — Granularity

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC BY 4.0

When does a video make sense within a teaching and learning scenario? Educational videos can be used in “different learning scenarios and forms of teaching and events” (Aldrian 2019: 5). They can be used in depth (Sailer/Figas 2015: 78; Aldrian 2019: 5), as a supplement (Aldrian 2019: 4), to provide variety (Aldrian 2019: 5), for preparation or follow-up (Aldrian 2019: 5) or as a primary source. Their field of application ranges from face-to-face teaching or live-streamed events to the field of blended learning (Aldrian 2019: 5 f.).

In principle, but especially in the context of blended learning, videos can be of a preparatory or follow-up nature or fulfill a corresponding didactic function (Aldrian 2019: 5). Especially in flipped or inverted classrooms, they can serve as a central source for learning or at least as a starting point for what is covered in the characteristically subordinate contact time or in the attendance phases (Aldrian 2019: 5). The same also applies to online courses, so-called MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses), which can often be completed without an appointment and at any time. Videos play a central role in conveying the course content (Ebner/Schön 2017: 4). Interactive elements are often also used in MOOCs (Sailer/Figas 2015: 78, Aldrian 2019: 6) in order to improve learner motivation (Aldrian 2019: 6).

In connection with the term hybrid teaching mentioned at the beginning, which has been used many times (Reinmann 2021), reference should be made to the live streaming of a lecture in presence, in front of a presence audience for a simultaneously virtually connected audience: Theoretically, the face-to-face event can be attended from any location thanks to video streaming. (Even though two “media” — presence and virtual space — “collide”. The best that can be achieved for both media is a compromise. More on this in part 3 of this blog series).

The taxonomy of the US psychologist Benjamin Bloom can be used to determine the didactic function of a teaching and learning video. The revision of the levels by the US educational scientist David Krathwohl can also be considered. The taxonomy can be used to classify or determine learning objectives, i.e. what learners should ideally “ultimately” be able to do in the course of learning and teaching videos or through their contexts. Benjamin Bloom’s stages are known to be the following: remember (recall knowledge), understand (summarize, categorize), apply (calculate, perform), analyze (differentiate, compare), evaluate/reflect (critically and reasonably examine), generate/create (conceive, realize).

The potentials (and emerging hurdles) of teaching and learning videos mentioned here will be explored in greater depth in the next parts of our blog post. First, however, we would like to focus on an orientation factor in the design of an educational video that has already been mentioned several times — the multimedia principles:

Orientation for didactic design (including teaching and learning videos) — Multimedia principles

The multimedia principles offer assistance in weighing up the use and combination of media — multimedia — and in designing it in concrete terms. In view of the multimedia nature of the moving image, they can also be consulted in the field of educational videos. These principles originate from the pen of the American psychologist Richard E. Mayer, in particular his work on multimedia learning, which has been published in several editions since 2001. Mayer’s principles are more than just theories; they are based on empirical findings.

Mayer’s considerations are not only used in the context of didactics, but also fundamentally in communication, even in the field of advertising. The number of multimedia principles varies greatly — depending on the edition of Mayer’s work: Mayer has added further principles to the catalog in recent years. We present an abridged version here.

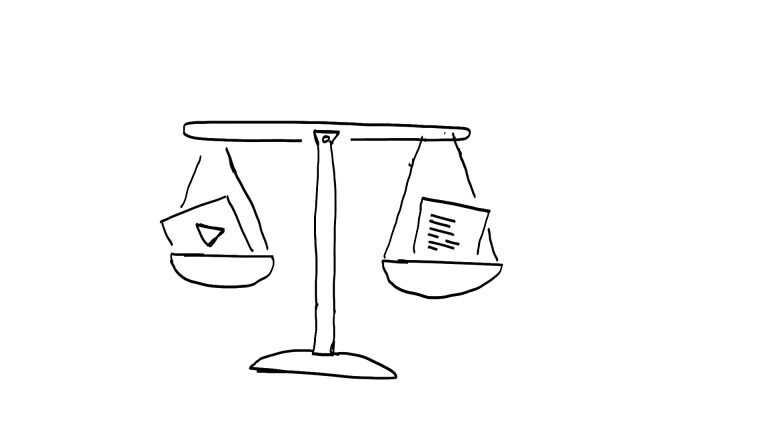

Weighing up design didactically — with the help of multimedia principles

Image by Sönke Hahn, released under CC BY 4.0

A cognitive learning model

Mayer’s concept of multimedia principles is based on a cognitive learning model for human information processing (Mayer 2021: 40 f.) and a corresponding idea of the processes in the brain. Working memory plays a central role in this. Working memory is essentially the human decision-maker associated with consciousness (Held/Scheiter 2019: 70 f.). It is the conscious interface between perception and long-term memory (Meyer 2020: 183). Working memory is the starting point for conscious action (Jank/Meyer 2020: 183). Working memory does not only draw on what is stored in long-term memory. Rather, it can also be the starting point for storing input in the long term or transferring it to long-term memory, which should certainly be a concern of teaching. Such knowledge can in turn be used in working memory and so on. In all these processes, working memory forms, creates or uses simplified mental images (Mayer 2021: 40 ff.). This is because working memory only has a limited amount of resources — in terms of the amount of data and the retention time of this data (Zoelch/Berner/Thomas 2019: 27 ff., Mayer 2021: 41).

In this model of learning, on which Mayer’s work is based, it is assumed that sensory impressions pass through the sensory memory following our sensory organs in order to enter working memory (Mayer 2021: 40 f.). The focus of the model is primarily on acoustic and visual information. This is because, in this model, they each enter working memory via a separate channel (Mayer 2021: 40). In this machine-like metaphor, the working memory holds resources for the processing of the two channels and the information brought to it. The “incoming” data sets are related to each other: The word cat very probably gives rise to the image of a cat. When we see a cat, we hear the word cat internally. (Mayer 2021: 41) This means that if only one channel is used when conveying new information to be learned, the resources of the other remain unused. Or if acoustic and visual information are very different, the working memory has a lot to do or is approaching overload. However, if both channels are used to capacity, “more” can potentially “happen” in the working memory. And this brings us specifically to the multimedia principles:

The principles

- Multimedia principle: People learn better from a combination of images and words than from words or text. This is because the combination can promote links in the working memory instead of just forming one-sided ideas. (Mayer 2021: 117)

- Coherence principle: Decorative elements without didactic added value should be avoided. Otherwise, resources on the part of learners are at risk of being diverted away from the actual teaching perspective. (Mayer 2021: 143)

This also refers to Mayer’s image principle: “Simply” displaying a static photo of a person to be heard verbally, i.e. the lecturer, next to the slides can be distracting. The static image without gestures and facial expressions looks bizarre. This threatens to make learning more difficult. (Mayer 2021: 331)

Caution: It should not be inferred from this principle that it does not matter how something “looks”. A uniform design brings consistency and provides a common thread — even in the transition from the video to other course materials. Aesthetics can also be seen as added value. Aesthetics can lend the work more credibility (Yablonski 2020: 59) and help any material to be retained in the long term. - Signal principle: Highlighting or emphasizing what is shown verbally or visually can promote better learning. This provides orientation, makes connections clearer and facilitates the creation of any mental representations. (Mayer 2021: 166)

- Redundancy principle: The simultaneous occurrence of written and spoken text (≈ reading aloud a visible or readable text) can impair learning. This is because identical information overlaps and has to be reconciled with difficulty. (Mayer 2021: 186)

- Contiguity principle (Mayer 2021: 207): Elements that belong together — e.g. text and graphics — should be positioned next to each other instead of at a great distance from each other. In the case of printed works, graphics should therefore not disappear in the appendix. This can lead to a loss of orientation.

- Segmentation principle (Mayer 2021: 247): Segmentation into smaller sub-units, which is gradually visible or emphasized, can promote the processing of what is shown and the structuring of the input — as opposed to a completely uninterrupted flow.

A balance must be struck here: between strong and in turn disruptive breaks and a flow that also creates connections.

Segmentation may be reminiscent of so-called chunking. Chunking refers to the processing of small units, particularly by working memory, or the consolidation of information into corresponding units (Zoelch/Berner/Thomas 2019: 27 f.). However, this process can be facilitated by the processing of information. In this regard, reference can be made to a field that experience has shown to be underestimated, the field of typography: subdividing as the “grouping” (Zoelch/Berner/Thomas 2019: 28) of a telephone number, for example, which is related to chunking, can help to make the number easier to remember or at least easier to type. - Preparation principle: Basic names and terms should be known to learners in advance of their “meeting”. This is because dealing with “involved” terms while explaining complex contexts makes understanding more difficult. (Mayer 2021: 265)

At this point, we also touch on a concept that can or even should be dramaturgically reflected in the structure of a video as a teaser or introduction: All the people or factors “playing a part” should be introduced before their relationship to each other is explored in greater depth. - Modality principle: If graphics or animations are to be explained, verbal information is more suitable than written text. In this case, there is no need to switch back and forth between image and text. Learners can focus more strongly. (Mayer 2021: 281)

- Personalization principle (Mayer 2021: 305): This refers to the fact that a colloquial or target group-specific style in teaching can facilitate learning. A personal approach can also be helpful — not only stylistically, but also in the form of a teacher who appears in person or an avatar. According to Mayer (2021: 305), the human component goes so far that a machine voice is more likely to be rejected than a human-looking voice.

This principle can be linked to Mayer’s embodiment principle (Mayer 2021: 341), which states that a lecturer should not just stand next to the image. Rather, they should interact with the image (gesturally) so that a connection to the facts (≈ signal principle) and ultimately to the learners is encouraged. - Immersion principle: Immersive media can provide a comprehensive insight into any given subject matter. Otherwise, a certain distance, as a 2D representation of a 3D fact, can create added value through abstraction. It is therefore important to weigh things up. (Mayer 2021: 357)

To classify: Immersion is understood by Mayer as an illusory, photorealistic, three-dimensional simulation, as virtual reality — as opposed to immersion in any kind of real to abstract space, work, etc. ≈ immersion in the world of a novel (Hahn 2018). - Activity principle: Guided, even prompting, immediate exercises and/or tasks that may take place after each section (≈ segment) can reinforce what has been learned. (Mayer 2021: 370) In this context, so-called h5P videos and the interaction they enable should develop potential in the field of teaching and learning videos.

Multimedia principles and cognitive learning model — Notes

Typical of models and their simplifying potentials: The cognitive in the cognitive learning model may suggest that this is about purely objective thinking versus the emotionality of the unconscious. Of course, the distinction between two systems — an explicit, conscious, rational one and an implicit, unconscious and emotional one — within our brain is of a theoretical nature (Kahneman 2012: 28 f.). In practice, working memory is also likely to be more or less emotionally influenced — according to Scheier and Held (2019) in a graphic representation of the two systems. This is probably also why Mayer’s statements regularly go beyond the factual: for example, with regard to a bond between the audience and the teacher that promotes learning, including an emotional bond.

Mayer’s model may then create the impression of a certain directionality. At first glance, it may conjure up analogies to a funnel principle: As if something could be instilled in people. For this reason, reference should be made here to constructivism. This “epistemology” (Meyer 2021: 286 f.) postulates a quasi-individual, conditionally conscious construction of an equally individual view of the world. Accordingly, learning is also based on a foundation of subjective experiences, values, beliefs, orientations and patterns. As a result, we must understand multi-channel utilization primarily as potential. Guarantees of success in terms of a teaching person can never be given even for those measures that fully comply with the principles. Personal characteristics and/or preferences of learners always play a role. In this respect, as a condensation of the words of the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann (1997: 212): Communication is improbable. And thus also teaching in the sense of a 1:1 transfer. This should not be discouraging, but shows how important it is to have a well-founded concept and design for teaching and learning videos and to weigh up their use. The constructivist view also shows that it is important to anticipate the target group of any teaching and learning videos. The relevance of multimedia principles should therefore lie in better addressing the “working memory” bottleneck with regard to teaching and learning.

Bottleneck working memory: If not expandable, then make the best possible use of it.

Image by Sönke Hahn based on Sarah Brockmann, released under CC 0 (1.0)

Conclusion on the first approach to the field of teaching and learning videos

We have cultivated the field. Because we have made a basic definition of what characterizes educational videos: Teaching and learning videos are audio-visualizations that can be accessed independently of time and place, if necessary, and are didactically prepared and categorized. We have briefly named format categories for teaching and learning videos: Lecture or presentation on video (live, as a recording), explanatory videos and demonstration videos. We have explicitly pointed out the importance of didactic and communicative classification. This has revealed initial hurdles, but also potential: Teaching and learning videos are time-consuming to plan and implement. However, videos are also in vogue, they are likely to meet a need of learners and have the potential to illustrate facts in a dynamic and catchy way.

In the next part of this blog post, we will expand on these impressions: We will define formats in more detail and contrast these with processes or techniques of realization. The next post will be published on April 22, 2022 — and can be accessed here.

To continue reading — here are the next parts of our series on teaching and learning videos:

About the authors

Franziska Bock, M. A. and Dr. Sönke Hahn are research associates of the project “OER-Portal Niedersachsen”: twillo — Lehre teilen. Bock is active in the field of university didactics and deals with questions of writing didactics and the conception of reusable teaching and learning materials. Hahn is an interdisciplinary scientist, filmmaker with international performances and multiple award-winning designer. As part of the Emden/Leer University of Applied Sciences, Bock and Hahn see it as their mission to go beyond good content to advance teaching as such.

References

Aldrian, S. (2019): Teaching video. Center for University Didactics. University of Applied Sciences of Business, Graz. URL: https://www.campus02.at/hochschuldidaktik/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2019/09/Lehrvideo.pdf (retrieved on 15.03.2022).

Baumgartner, P. (2004): “Didactics and Reusable Learning Objects (RLOs)” In: Carstensen, D. / Barrios, B. (eds.): Campus 2004. Are digital media at universities coming of age? Waxmann: Münster, New York, Munich, Berlin; pp. 309–325.

Bloom, B. (1984): Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Allyn and Bacon: Boston 1956, Pearson Education.

Burkhard, R. (2019): Communication science. Böhlau: Vienna, Cologne, Weimar.

Ebner, M. / Schön, (2017): Learning and teaching videos: Design, production, use. E‑learning handbook. 71st supplement (October 2017). 4.61. S. 1–14.

Hahn, S. (2018): The sixfold nature of immersion: an attempt to (discursively) define a multi-layered concept URL: https://www.academia.edu/35937976/Die_Sechsfalt_der_Immersion_Versuch_der_diskursiven_Definition_eines_vielschichtigen_Konzepts (15.03.2022).

Harder, S. (n.d.): Teaching videos. Possible uses in part-time studies. URL: https://www.uni-rostock.de/storages/uni-rostock/UniHome/Weiterbildung/KOSMOS/Lehrvideos.pdf (retrieved on 15.03.2022).

Hickethier, K. (2007): Film and television analysis. Metzler/Poeschel: Stuttgart.

Jank, W. / Meyer, H. (2020): Didactic models. Cornelsen: Berlin.

Kahneman, D. (2012): Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002): “A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview” In: Theory into Practice, 41 (4); pp. 212–261

Lehner, M. (2020): Didactic reduction. Beck: Bern.

Luhmann, N. (1997): The society of society. Suhrkamp: Frankfurt a. M.

Mayer, R. E. (2021): Multimedia Learning. Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, H. (2018): Guide to lesson preparation. Cornselsen: Berlin.

Persike, M. (2019): “Videos in teaching: effects and side effects” In: Niegemann, H. & Weinberger, A. (eds.): Learning with educational technologies. Springer: Germany.

Reinmann, G. (2021): “Hybrid teaching — A term and its future for research and practice” In: Impact Free, 25, Feb. 2021.

Rosenbaum, L. (2018): “Youtube — Developing educational videos into an interactive learning experience” In: Blog E‑Learning Zentrum Hochschule für Wissenschaft und Recht Berlin. URL: https://blog.hwr-berlin.de/elerner/youtube-lernvideos-zu-einem-interaktiven-lernerlebnis-weiterentwickeln/ (accessed on 15.03.2022).

Sailer, M. / Figas, P. (2015): “Audiovisual educational media in university teaching. An experimental study on two learning video types in statistics teaching” In: Educational Research 12 (2015) 1, pp. 77–99.

Schanze, H. (ed.) (2002): Metzler Lexikon Medientheorie — Medienwissenschaft. Stuttgart.

Scheier, C. / Held, D. (2019): “The neuro-logic of successful brand communication” In: Häusel, H. (ed.): Neuromarketing. Insights from brain research for brand management, advertising and sales. Haufe: Freiburg, Munich, Stuttgart; pp. 65–96.

Schnell, R. (2002): Media aesthetics. On the history and theory of audiovisual forms of perception. Metzler: Stuttgart.

Yablonski, J. (2020): Law of UX. 10 practical principles for intuitive, human-centered UX design. O’Reilly/dpunkt: Heidelberg.

Zoelch, C. / Berner, V. & Thomas, J. (2019): “Memory and knowledge acquisition” In: Urhahne, D. / Dresel, M. & Fischer, F. (eds.): Psychology for the teaching profession. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg; pp. 23–32.

This article by Franziska Bock and Sönke Hahn is licensed under CC BY 4.0 unless otherwise stated in individual content.